COMMUNITY SCIENCE NEWSLETTER

BEHAVIOUR IS A MIRROR IN WHICH EVERYONE SHOWS THEIR TRUE IMAGE:

Researchers at UniSC work with the Coast’s locals to reveal the behaviours that underpin healthy ageing

Research team: Daniel Wadsworth, Kristen Tulloch, Hattie Wright, Corey Linton, Jesse Baker, Samantha Fien, Helen Szabo, Christopher D. Askew, Mia A. Schaumberg.

ARTICLE INFO

Article type: CORE CONCEPT

Issue date: 08/02/2024

Issue No.: 1

Authors: Dr Dan Wadsworth, Dr Kathryn Broadhouse

Original peer reviewed article: doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2022.11.005

REVIEWERS

Geoff Clarke

B.Ed. (Adult and Workplace): Boilermaker/Blacksmith

Judith Mackenzie Ross

Semi-retired, Commonwealth Government worker, writer of digitised weekly travel newsletters

Jason Law

CEO: DRAUGHT ANGELS

ARTICLE SNAP SHOTS

Rationale: why did we do this work? Our behaviour and perceptions of health contribute towards our own health, and that of our peers, but are often presented in research within large data sets and/or drawn from people with suboptimal health. Therefore, individual voices and experiences get lost. We wanted to understand local healthy seniors’ perceptions of health so as to benefit the local community. Furthermore, we wanted to understand what behaviours support healthy ageing. If we can identify the behaviours of people ageing healthily, we can then all model them and improve our own health as we age.

Novelty: what’s new in this work? Addressing the above gap, this work provides context to previous research by presenting key competencies (behaviours) that support healthy ageing, as identified by a group of healthy older Australians living on the Coast.

Relevance: Why does it matter to you? Fostering the behaviours presented below may support our own healthy ageing journey, whilst future clinical practice integrating them can guide public health initiatives and healthcare policy.

"This article talks about the importance of behaviour and attitude towards healthy ageing. Hearing from elders who are ageing healthily and modelling their behaviours may make a difference to your life and potentially longevity. For elders already ageing well, this paper does not provide anything new but provides confirmation that they are on the right track”.

QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS

REVIEWERS: The article would benefit from explaining what suboptimal means and explaining in more detail what competencies mean in this context. For many competencies are mastery of a tactile skill like welding or riding a bike.

RESEARCHERS: "The use of ‘suboptimal’ reflects that health is not a definitive term, but rather something that people experience on a linear scale – we wanted to acknowledge that ‘healthy’ ageing is subjective, and also acknowledge that optimal may mean different things for different people. Importantly, the term ‘suboptimal health’ is being introduced in the research sphere to recognise that there is a space between being as healthy as you can and diagnosed with a specific condition, for example. We use the term ‘competencies’ to differentiate from specific health behaviours that are often presented in literature. We agree that these are very much ‘skills’, and indeed a key message from this paper is the need to foster these competencies (or skills) which may underpin healthy ageing."

INTRODUCTION

Healthy ageing is the process of developing and maintaining the functional ability that enables wellbeing in older age; in other words, it's being able to continue to do what makes us happy. It is an active process we must manage and work on continuously. Everyone will experience gradual changes in their mental and physical abilities as they age. To scientists who study healthy ageing, these changes are known as normal cognitive and functional decline. If we start to decline more rapidly over time this can be a sign of unhealthy ageing and disease. We are all at risk of unhealthy ageing and developing age related diseases such as dementia. There are many factors that increase this risk such as loneliness, smoking, alcohol abuse and physical inactivity. The more risk factors someone has the more likely they are to develop age-related diseases. Equally, the fewer risk factors someone has the more likely they will age healthily.

Many risk factors for unhealthy ageing are down to lifestyle and can potentially be eliminated by changing our behaviour. We therefore have a certain amount of control over how we age.

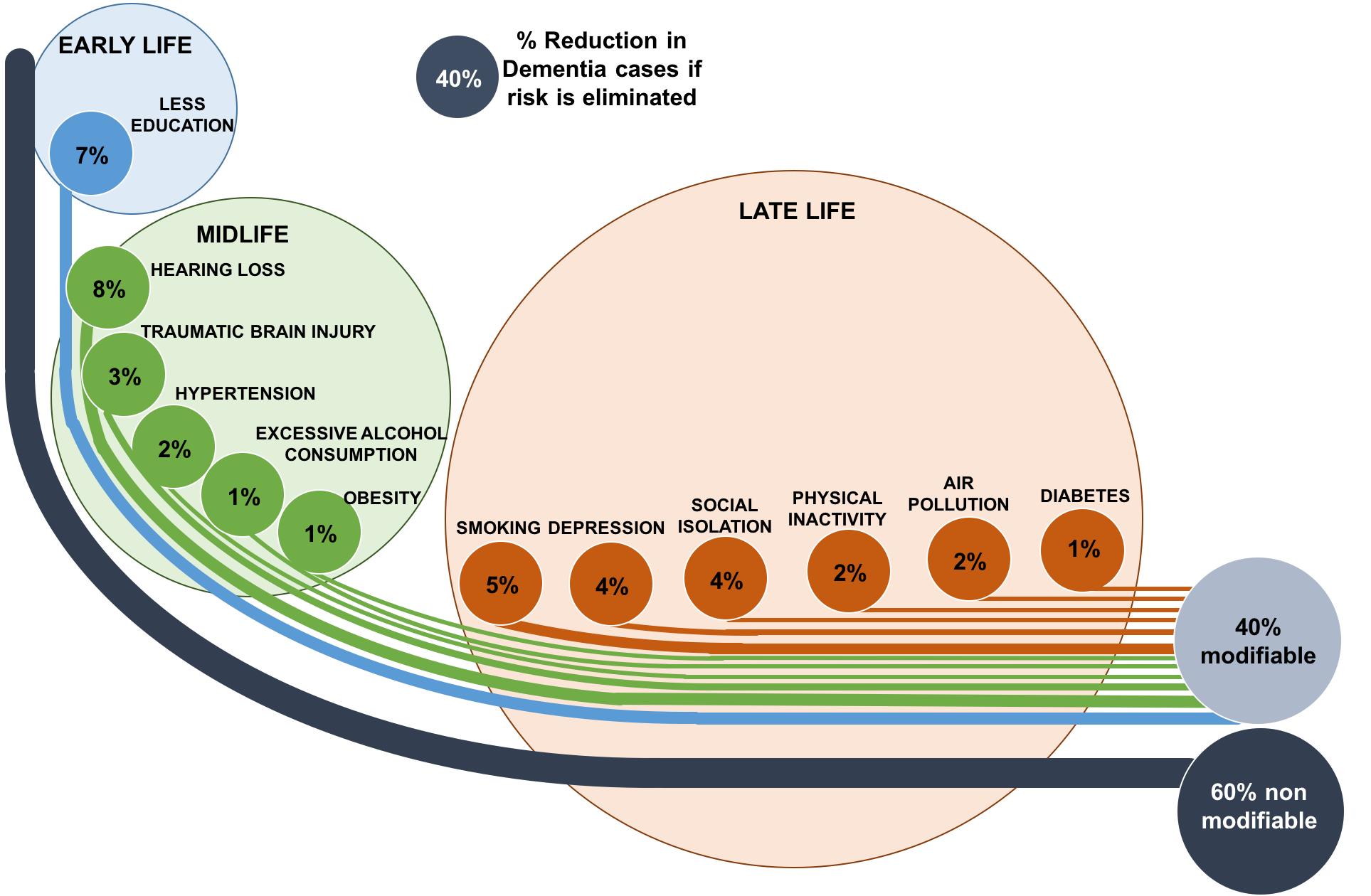

Behaviour can predict outcome. Researchers have spent the last few decades identifying, and more importantly, quantifying these modifable, lifestyle-related risk factors. They are the usual suspects – poor diet, smoking, loneliness, etc., but by combining thousands of studies from all over the world we can now calculate the associated risk of obesity, excessive alcohol consumption, social isolation and physical inactive and its impact on our own chances of ageing well. The figure below has been recreated from data presented in The LANCET and shows the percentage of dementia cases that could be eliminated if we reduced certain lifestyle factors throughout our life.

The numbers are in and show that if we all follow a healthy lifestyle we could eliminate up to 40% of dementia cases worldwide. Putting numbers to things is compelling as we all know what we need to do to stay generally healthy but it is often hard to change our behaviour to do so.

Your behaviour and habits underpin not only who you are now, but how you will age later.

Incorporating the above positive lifestyle components into our daily lives allows us to develop and maintain wellbeing, but requires us to modify our behaviour somewhat to do so. This can be very difficult. Researchers at UniSC are now trying to understand what set of behaviours and competencies healthy ageing adults on the Coast possess that support age healthily. We are moving on from defining healthy lifestyle factors and are now asking healthy ageing adults, the true experts, about their approach and perception of ageing healthily.

We are pretty good at understanding our own health. Our perception of our own health is not only closely related to our real medical health status, but a positive perception of health is crucial to ageing healthily and partly determines our ageing experience. Negative stereotypes and poor self-perceptions of ageing are linked to a lower likelihood of adopting and maintaining health-promoting behaviours, resulting in reduced health ageing [i].

Living in an ageist society that constantly views ageing negatively, one is more likely to perceive their own health negatively and have bad health experiences as they age. The positive is that the reverse is also true, making the sharing of positive experiences of health and healthy ageing a powerful tool.

To understand how we can age healthily we need to understand the behaviours of those already doing it. To date, most research investigating perceptions of ageing and health does not consider the individual, but rather focuses on groups of similar individuals. This is useful when we want to understand healthy ageing strategies that can be applied to large groups of people, but we miss important specific information that may provide more focused help and insight. Furthermore, much of this work also comes from groups of people with suboptimal health, meaning we may be missing some important information. In this study we explored the experience of healthy older adults living on the Sunshine Coast to understand and learn from their individual perspective. You can view the peer-reviewed scientific paper here doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2022.11.005.

[i] (Chang et al., 2020; Lamont et al., 2015)

AIM: examine healthy older adults’ perceptions of health and healthy ageing and identify the core behaviours that support ageing well.

METHODS

Participants: Twenty-two, English speaking, healthy older adults, living independently in the Sunshine Coast community, aged between 61–83 years (15 female, 7 male) participated in our study. Health, Cognitive Function, and Wellbeing measures were taken to ensure participants were all in good health.

Focus groups: Participants joined one of six focus groups. The focus groups lasted for 60–90 minutes and were recorded and moderated. After introductions and a broad discussion around “health” (“what does being healthy actually mean to you?”; “how do you feel about your current health and wellbeing?”), discussions were guided through the importance, the motivators, and the influencers of three broad modifiable lifestyle components: 1. physical activity, 2. diet, and 3. psychosocial elements (how a person copes and accepts their own thoughts and behaviours in connection to external factors, such as friends, family and community). The moderators encouraged all to share, ensuring sufficient opportunity for everyone to express their views and experiences. Each focus group was closed with a summary of the broad ideas allowing for reflection and elaboration.

"We put ourselves in the researcher’s shoes to brainstorm additional approaches for the guided sessions to tackle the complex problem of asking people about emotional topics. We suggest that future studies looking to go deeper and draw out the personal journeys of the participants could be structured over several sessions. An information sheet could be provided initially as a point of reference, followed by an informal chat, then structured focus groups."

QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS

REVIEWERS: The size of the research group was very small and that there was an imbalance in female to male participants that may impact the findings. Can the authors comment on this?

RESEARCHERS: "The reviewers are quite right to pick up on the gender imbalance of participants in this study. The demographics of our sample reflect that often seen in health-based research – older, white females with a good level of education and socio-economic status. This brings with it issues, as although the findings are quite representative of the demographic here on the Sunshine Coast, they may not fully reflect competencies/healthy ageing journeys of other cohorts of people."

REVIEWERS: The time frame for talks may have been too short to discuss a topic as rich and complex as healthy ageing. Did the researchers feel that they needed longer for these focus groups?

RESEARCHERS: "We definitely could have continued to talk more in some of these sessions! After the first focus group, we amended our schedule to allow for more time, and when completing our analysis we reflected on just what a rich data set we had collected!! We didn’t feel that people were cut short during our sessions – to the best of our knowledge, everyone had the time needed to speak on each topic."

RESULTS

Transcripts of the recorded discussions were thematically analysed, a qualitative analysis technique whereby researchers familiarise themselves with the transcripts, assign initial codes, search for themes, review themes, define and name the themes, write up findings. Seven major themes were identified that influenced experiences of healthy ageing: 1. know thyself, 2. knowledge and information management, 3. choices, agency, and control, 4. autonomy and flexibility, 5. being strategic, 6. community connections, and 7. getting more out of life.

Theme 1. Know thyself: The importance of having an awareness of individual (“being healthy is being in tune with your body”) and environmental (“to be out in nature it’s good for the soul”) factors that are perceived to influence health was a major theme. Participants spoke about the importance of understanding one’s own identity, preferences, ways of being, and needs—whether dietary, physical, psychological, or social—and how these can change over the lifespan, especially through the transitions of life (“You’ve got to be able to deal with things that are thrown at you and especially in this world”). This further involved a degree of accepting (“You may have your aches and pains, but hey, that’s part of ageing”) and celebrating (“I had a great life and am still having a great life”) changes, both within themselves and society.

Theme 2. Knowledge and information management: Possessing sufficient knowledge and understanding of health (i.e., health literacy) was a common theme across groups. Participants spoke about the importance of having appropriate knowledge of health (“But first you’ve got to be aware of [the markers of good health]. A lot of people aren’t, and I think that’s, that’s a challenge”); how to access, process, evaluate, and use information in relation to health (“we’ve got such an overload of information that you think you’re doing the right thing and then ‘oh, no, no, you shouldn’t do that, you should do this’, and it confuses”); and how to maintain health through self-management strategies. Participants reported using a range of formal and informal information-gathering processes (“in terms of information and knowledge. I don’t think I can say that’s from any one place”; “I’ve actually gone to the trouble to listen to a 10h set of podcasts on microbiomes and things like that”; “Whereas an older group prefer the paper.”), but recognised the difficulties in finding good-quality information (“there’s a lot of rubbish on the internet, not scientifically based”).

Theme 3. Choices, agency, and control: The importance of taking responsibility for one’s own health through the choices made (“We’ve got the opportunities. It’s up to the individual to be aware of it and to have the confidence to go forward and inquire about it.”), coupled with an awareness of the influence of factors outside the individual’s control (“[before we moved] it’s two hour drive the mountains, two hours to the sea, the things we wanted to spend time at, we had to drive all the time”), was recognised as an important determinant of health. Participants identified that although there are lots of ways to be “healthy”, navigating the choices to be made required deliberate and active involvement on the part of the individual (“[exercise] has become a deliberate thing [for me]”). In this theme, individuals’ application of knowledge was evident in not only smaller daily decisions (“I think you can excuse all sorts of things for being unhealthy. But you’re the only one that’s putting something in your mouth, and you’re the one that’s not moving when you’re talking about people sitting”) but also larger questions of lifestyle choice, with the recognition that such choices were easier to make with adequate resources (“And I think as we get older, we need to have access to medical things. And better public transport. That’s definitely not here”).

Theme 4. Autonomy and flexibility: Self-determination was a small but strong theme. Individuals specifically identified a need for autonomy and flexibility in navigating their own health (“there is too much focus on telling us what we can eat and what we shouldn’t need”; “I did a couple and I just thought ‘I’m not gonna stick with this’, because it was sort of not motivating me”). Although participants reported that in some instances, they had inadvertently created their own restrictions or pressures around health choices and behaviours (“I started a diet once and it just drove me insane”, “Sometimes I just really get annoyed with [routines]”).

Theme 5. Being strategic: Consciously developing and employing deliberate strategies to support health, values, and beliefs relating to healthy lifestyle behaviour were commonplace (“The gym is there to prepare you for the upright and breathing out in the sunshine. The gym is not the end of it, it’s the beginning of it and you’ve got to set objectives, such as a run or a trek.”; “If I don’t want to eat it, I won’t put it in the fridge”). This theme appeared as a natural progression from earlier themes: participants demonstrated extensive intellectual engagement and reflection of those thought processes with health outcomes and goals, developing personal systems, or routines to deliver consistency of adaptive health behaviours with foresight and planning (“.forward planning makes a huge difference if you’re making a big change from one stage to another, you’ve got to think about how you’re going to fit in”). This was often reported with a holistic approach to health, whereby participants considered different aspects of their health and adjusted their lifestyles accordingly (“When I moved down here when I retired six years ago, my wife virtually kicked me out and said go to that men’s shed’ and it was the best thing. If I had waited two years or a year or something, I wouldn’t have gone”).

Theme 6. Community connections: The value and importance of community and social connections for health were apparent throughout, with many discussing what such connections brought to their life (“Hanging out with young people is pretty rewarding”). Participants remarked upon the depth of interactions with specific recognition that both richer (“I’m really lucky, I’ve got two really good friends…they can share the good times and bad times. We’ll talk absolute crap, but we do have ... those common threads with us. We’ve known each other 20, 30 years.”) and more casual connections (“sometimes I walk out and just walk down the street to see if anybody else’s around and have a chat”) were valuable, and how such connections could be leveraged to benefit other health behaviours such as exercise, or the ritual of sharing food. Predominantly, community connections were discussed as facilitative for health (“[my activity levels] increased dramatically. I had to move into this new [over 50s] place in March, and there’s just so much to do.”). Many noted retirement and consequent changes to community engagement.

Theme 7. Getting more out of life: A final theme was the determination to maximise the benefits and get the most out of life. Primarily, discussions revolved more around maintaining current levels of recreation or functionality (“if you lose one of those [mental or physical health] then you have to deal with it”; “It’s better to be in the top 10% than to be in the rest. You can do what you like.”) and ensuring that good quality of life continued for as long as possible (“So that’s the reason I do exercise and stuff. Because I still want to be able to squat down with the grandkids”; “I want to be mobile, I want to be doing. I don’t want to miss anything when that opportunity comes along.”). Discussions on this theme showed strong links to autonomy and agency, but with greater consideration of the aspects of life that provide enjoyment.

CONCLUSION

The purpose of this study was to understand healthy older adults’ perceptions and practices of healthy ageing so that their expert lived experiences can be a positive stereotype, providing direction for individuals, future public health initiatives, clinical practice and care. Participants in this study spoke across seven major themes that underpinned their experiences of healthy ageing.

The findings presented here are in some ways obvious. Much like the fact that poor diet and no exercise increase your risk of age related disease, a proactive approach to your own health will help keep you healthy. The behaviours identified here highlight the importance of deliberate actions, interactions, and choices; such actions bring meaning and purpose to life, which is positively associated with wellbeing[i]. Fundamentally, the discussions here confirm the importance of behaviours that support social connections, being physically active, and following a healthy diet. The difficulty is that incorporating these aspects into our lives so they become a part of who we are takes mindful practice and time. These findings serve as a reminder that we all need to start practicing these behaviours regardless of age, as we all want to age healthily throughout our lives.

When we become ill we all want treatment plans that promise a quick, effective recovery. Unfortunately age related diseases and age related decline are very different from most aliments we will experience in early and mid life. They are brain based and due in part to our own lifestyle and the ongoing effects of time; to date we have no pharmacological cure for them and we may never have. Researchers are now turning to preventative strategies. When building resilience to cognitive decline it stands to reason that treatment will not be in the form of drugs but a long term practice of improving your brain health. For the individual reading this article these findings provide a checklist, a plan and a reminder to tick off each day, week or month to continue the building of meaningful, healthy lives.

[i] (Dahl & Davidson, 2019; Ten Bruggencate, Luijkx, & Sturm, 2018)

"This study is a good start, and these focus groups provided an opportunity for participants to be heard and for us to learn from that experience. However, we recognised that this is a very emotional topic, that care and time is needed to build a relationship with the participants. In the future we would like to see findings presented from discussions around complex topics of the human condition (i.e. religion, money, sex, sexuality, death and dying) to full understand what behaviours and attitudes are needed in the individual and society as a whole to age healthily and support healthy ageing."

QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS

REVIEWERS: How the researchers decided upon this guided session approach to acquire data and how they prepared for them? What was the researchers personal experience of this process?

RESEARCHERS: "These sessions were a real pleasure to facilitate, and learn more – as per the paper, we recognise the value in hearing from the true healthy ageing ‘experts’! If we were to dive deeper and explore some of the more complex topics highlighted by reviewers, the team would consider if focus groups or 1:1 interviews were a more appropriate method to take. from our experience often people can actually feel more comfortable to speak on such topics when others are doing so, but some may prefer the more personal/secure 1:1 interview – the latter has certainly been the case in a current related project exploring older adult’s experiences of poor mental health, for example. Focus groups were chosen for this project as they are known to be a good environment to safely elicit and challenge experiences and opinions in research – the natural flow of well-facilitate group discussion can encourage everyone to contribute. We tightly regulated how many people joined each session though, as small groups (3-5 people) have been shown to be optimal for such sessions. We went through a thorough iterative process to develop a suitable guide for our interviewers, based on 3 known functional determinants of health, which was supported by some deep discussion across our team of researchers and industry representatives."

REVIEWERS: How did the researchers feel about guiding these talks and how would they feel about conducting future studies looking into conversations around death and dying?

RESEARCHERS: "It’s great to see the foresight here, of how this work can set the foundations for future work – thank you! It was a real privilege to listen to everyone’s experiences and stories in this project, and it would be fabulous to build further and hear from more people. We note your suggested approach for future iterations with interest, and recognise the value of ongoing relationships with community members across various research projects – hopefully this is something that our Community Gateway project can help to support!! "

THE FOUR COMPETENCIES

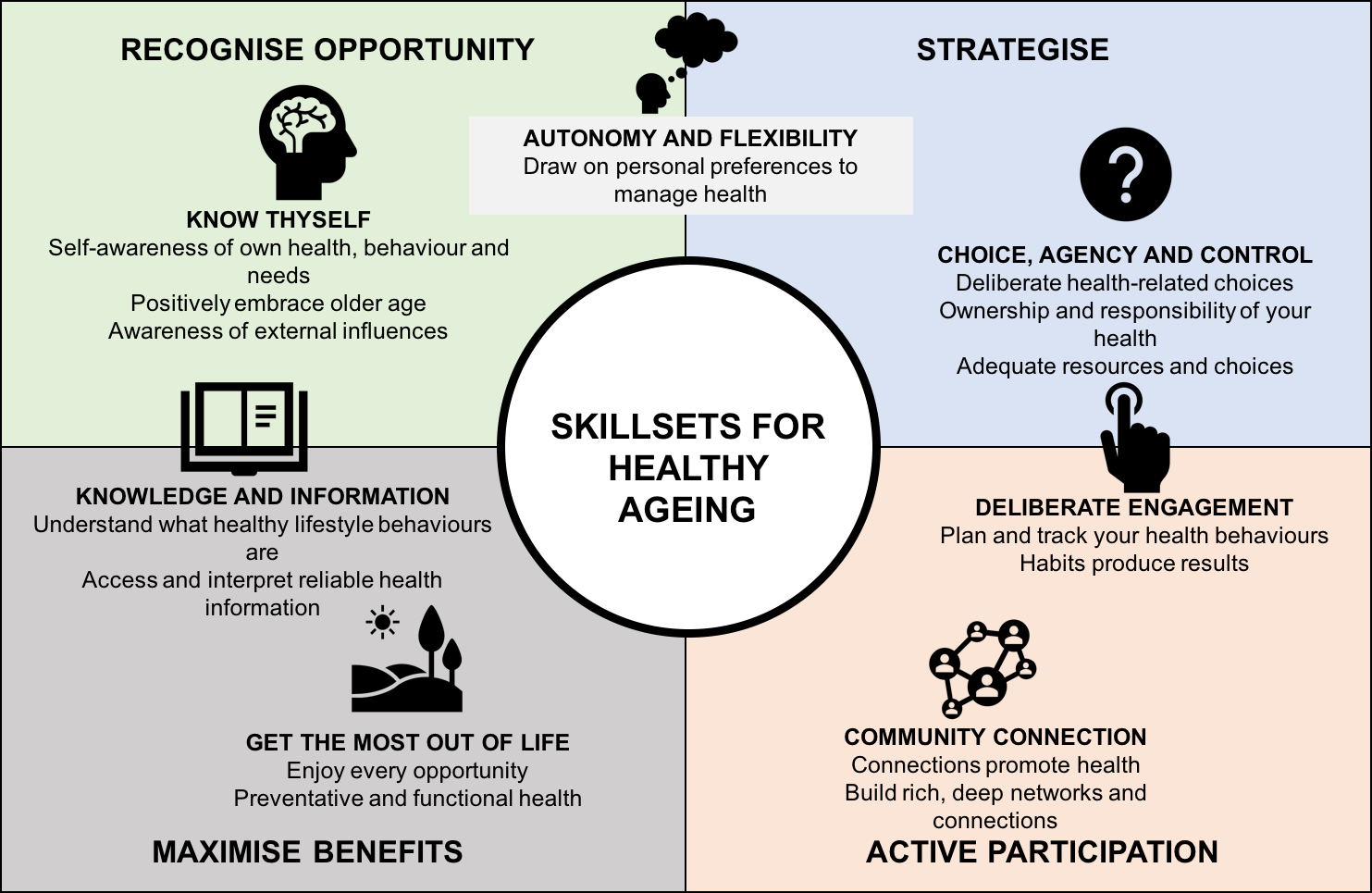

Also evident across this study, and key to maintaining our health as we age, is the underlying essence of self-regulation, self-efficacy, and empowerment that can enable us to make appropriate strategic choices, overcome barriers, and maximise our health benefits. Such skills also allow us to act in flexible and reactive ways, taking ownership of our health and responding to challenges, and enabling our ongoing functional capacity.

From the seven behaviours that our participants identified we have determined four overarching skillsets, or competencies, that will act as pillars of healthy ageing shown in the figure above. Practicing these behaviours each day will build your own skills in these four area. These competencies align with the four core principles of overall wellbeing[ii]: Awareness ∼ Recognise

Opportunity; Connection ∼ Active Participation; Insight ∼ Maximise Benefits; and Purpose ∼ Strategise. For the practitioners and policymakers reading this article, we should now focus on these competencies to empower people to adopt ‘healthy’ behaviours that are most appropriate to their specific settings/desires, and thus age well. As individuals, observing and working on these four competencies, adopting them into our lifestyle may provide the sense of wellbeing enabling us to flourish, as we age.

[ii] (Dahl & Davidson, 2019)

Looking to the future we need to understand the relationship between perceptions of health, adoption of these competencies/skillsets and our ability to navigate, recover from, and in some cases live with, age related diseases. We suggest that future research explores the perceptions of healthy ageing over time in diverse populations and regions. From a healthcare perspective, we propose that by adopting a broader competency-based approach to healthy ageing, encompassing these four skillsets in care for older adults across the functional spectrum, health practitioners can support older adults to recognise opportunities through a deep understanding of themselves and the available information, framing negative perceptions and challenges accordingly. From an individual perspective, adopting these healthy ageing skills in our daily lives, much like a mindfulness practice or exercise training plan, have the potential to empower us to develop and act upon strategic plans to maintain and enhance our own health.

If behaviour is a mirror in which everyone shows their true image, then building these skills into our daily behaviour will allow us to reflect our healthiest selves.

Email:HACA@info.edu.au

HACA acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the land on which we conduct our activities. We pay our respect to their Elders past and present and extend that respect to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples throughout Australia

COPYRIGHT © {2023} - HACA